Michael Porter’s influence on strategic management can hardly be overemphasized. While his work has come under increasing criticism, it remains vitally relevant. Porter has been able to answer much of the criticism, but the critics have also been able to spot some holes in Porter’s frameworks.

Michael Porter’s influence on strategic management can hardly be overemphasized. While his work has come under increasing criticism, it remains vitally relevant. Porter has been able to answer much of the criticism, but the critics have also been able to spot some holes in Porter’s frameworks.

In this post, I will examine Porter’s main frameworks for strategic analysis, the five forces analysis (industry analysis) and value chain analysis (relative analysis), and point a way towards a “Porter plus” approach that uses Porter’s frameworks as a basis, but adjusts and augments them with crucial insights from others, notably on dynamic capabilities.

For a comprehensive view on Porter’s strategic thinking that spans a large number of books and articles, I recommend Joan Magretta’s Understanding Michael Porter: The Essential Guide to Competition and Strategy, which collects and updates Porter’s thinking up to 2011. It also points at some of the criticism directed at Porter, although perhaps not to the most important pieces.

What is strategy?

According to Porter, strategy is the set of integrated choices that define how you will achieve superior performance in the face of competition. For Porter, competition to be the best, to do the same things as competition, but better, is nonsensical. Strategic competition is competition to be unique, to make different choices than your competitors, with the goal of making profits, not beating competitors.

One largely unsuccessful criticism leveled against Porter is the blue ocean – red ocean view, in which red ocean is the same as competition to be the best, and the desirable state, blue ocean, is a strategic approach that makes competition irrelevant. It is, however, not well-established that it would actually be possible to make competition irrelevant, and Porter’s frameworks enable analysis of competition also in situations where competitors are making different choices.

Industry analysis: the five competitive forces that shape strategy

For Porter, a crucial starting point for strategic analysis is analysis of the surrounding industry. Porter’s framework for this is the five forces analysis, which can be used to examine the state of an industry and the relative strengths of the different roles in it.

Porter’s key insight is that, on average, the industry a company operates in determines its potential profits. The relative profitability of many industries has remained extremely steady over long periods of time, with, for example, the pharmaceutical industry constantly near the top and the airline industry constantly near the bottom. Individual companies can affect their profits by understanding the forces that affect the industry they operate in.

One of the key difficulties in applying the five forces analysis is determining what an industry is. Porter’s rule of thumb is that for operations to be considered as part of the same industry, there should not be differences in more than one force, and no large differences in any of the forces. Here it is also crucial to recognize that an industry is not only a matter of product, but also of geography, so the number of analysis a company may need to perform can be quite big.

Rivalry among existing competitors. The more intense the rivalry between the companies within an industry, the less profitable it is. Usually this means that industries with more incumbent companies are less profitable. This contradicts some appearances: consider Coke and Pepsi, for example. From a consumer point of view, they appear to be fierce rivals, but actually they do not compete all that fiercely and are both highly profitable companies. Other causes for intense rivalry include slow growth of the industry and high exit barriers that prevent companies from leaving.

Threat of new entrants. The easier it is to enter an industry, the less profitable it is. Barriers to entry that can protect the incumbent companies include legislation and licenses, economies of scale (although here it is important to keep in mind that sufficient economies of scale can often be reached with a surprisingly low market share), switching costs for customers, and investments that would become sunk, such as industry-specific R&D or production facilities.

Threat of substitute products or services. The easier it is to substitute the products or services of the industry with different products, the less profitable it is. Substitution can often come as a surprise, because it is often a chain reaction with remote causes affecting an industry. For example, consider the increased demand of machine tools and decreased demand of injection molding machines as the mobile phone industry has moved toward machined housings to improve its time to market. On the other hand, electric cars threaten the machine tool industry from a different angle, as if the demand for internal combustion engines decreases, the demand for machine tools is also likely to decrease.

Bargaining power of suppliers. The greater the relative power of the suppliers over the companies in the industry, the less profitable it is. Powerful suppliers are able to capture the profits for themselves. One of the most difficult situations is when a supplier is a monopoly, the only provider of a product or service.

Bargaining power of buyers. The greater the relative power of the buyers over the companies in the industry, the less profitable it is. Powerful buyers are able to capture the profits for themselves. One of the most difficult situations is when a buyer is a monopsony, the only buyer for a product or service.

Criticism of the five forces analysis

As a dominant paradigm for decades, the five forces analysis has attracted its share of critics.

Are there more than five forces?

Perhaps the most common line of criticism is to elaborate on the various factors that can affect an enterprise, and to argue that there must be more than five forces at play. The suggested additional forces range from globalization and digitalization to the role of institutions, complements, and network effects.

Globalization, digitalization and the role of institutions. The weakest form of criticism cites various current trends as separate forces. However, this can clearly not be the case, because all such trends are of limited temporal scope, and as such cannot be general forces the effect of which should always be considered. All of these can be handled within a five forces analysis by enumerating the various effects they have on each of the five forces.

Complements. Complements are products or services that are used with the industry’s product so that the value of the two products together is greater than the sum of their values individually. A typical example is hardware and software: a computer without software is useless, and so is software without a computer. Porter has responded to this criticism by pointing out that unlike the five forces, the force that the existence of complements places on the industry is not clear, and that it is better to further analyze the particular complements in any industry through the five forces analysis. Complements can affect barriers to entry, threat of substitutes, and industry rivalry (increased switching costs or decreased possibilities for differentiation).

Network effects. Network effects mean that the value of the product or service is different depending on its other users. The classic example is the telephone: being the only telephone owner in the world would mean that the telephone is completely worthless. In recent times, network effects have become even more important, as they are central in various fights between ecosystems, for example in social networking sites and in mobile phones. However, network effects, too, can be further analyzed into effects on the five forces, mainly industry rivalry.

Thus, no uncontested sixth force has been discovered so far. However, the grain of truth in the criticism is that in order to be able to conduct a thorough five forces analysis, it is first necessary to conduct environmental analysis (demographic, socio-cultural, technological, macroeconomics, political-legal, and global trade) and stakeholder analysis to have a sufficiently accurate picture of the company’s operating environment.

Are industries static or dynamic? Who can affect change?

Another line of criticism sees the five forces analysis as presupposing a completely static environment, and argues that because the world is increasingly dynamic, the five forces analysis is outdated. A further step in this line of criticism is a claim that the five forces analysis presupposes that any changes in the industry structure are exogenous, whereas in reality companies are also able to shape the structure of the industry they are in.

Porter has been able to answer these critics as well by analyzing the options five forces analysis opens to a strategist:

Positioning the company. Five forces analysis can be used to choose the position of the company in the industry. This is the only use the critics who view five forces analysis as completely static have acknowledged.

Exploiting industry change. Five forces analysis can be used to claim new strategic positions in times of change. The critics who say that five forces analysis can only accept exogenous changes admit this much.

Shaping industry structure. Understanding the forces that affect the industry can also open up opportunities to change them. There is nothing in the five forces analysis that prevents companies from using the information they acquire to change the world instead of just accepting it as such.

Who can tell what is an industry?

Another line of criticism focuses on the definition of an industry. Granted, it is difficult to tell what is an industry, and sometimes it takes several attempts to figure out what parts of operations face the same forces and what face different forces. However, as long as the five forces analysis can provide valuable insights, some level of difficulty in its application is acceptable. Sometimes reinterpreting the industry a company is participating in can even open valuable new strategic options, turning the difficulty into an advantage.

The speed of change

Porter takes the position that industry structures are relatively stable, and change is usually slow. While not fatal to the five forces analysis, this has lead some critics to ask what is the strategic importance of building capabilities to rapidly react to change and to opportunities to create change. I will discuss this dynamic capabilities view more a bit later.

Thus, despite the criticism, the five forces analysis remains one the key analyses available for a strategist.

Relative analysis: value chain analysis and resource-based view

After analyzing the industry in general, it is time to turn to analysis of individual companies in it. Porter’s framework for doing this is value chain analysis.

Value chain analysis

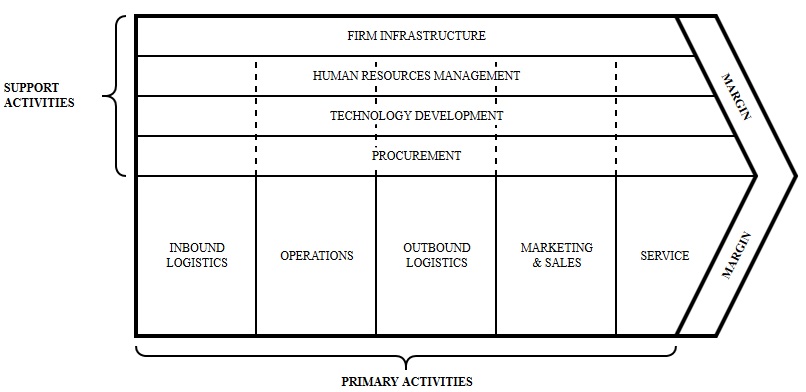

A value chain is the sequence of activities a company performs to design, produce, sell, deliver, and support its products. The aggregate of the value chains of different companies that brings a product to the end user is called a value system.

Picture: Michael Porter’s Value Chain from Wikipedia (CC)

Porter argues that in order to avoid competing to be the best, each company should strive to arrange its value chain differently from competitors in ways that create a competitive advantage for the company. Therefore, the value chain analysis requires information on the value chains of key competitors (competitor analysis) and compares your own value chain to theirs. The comparison should include evaluation of both whether it is practical to perform all of the same activities, and whether the activities can be performed in different ways to either increase customer value or reduce costs.

Here lies one of the major weaknesses in Porter’s thinking. Porter uses the term operational effectiveness (OE) to refer to a company’s ability to perform similar activities better than its competitors. While Porter acknowledges that operational effectiveness can result in temporary competitive advantage, he does not see a possibility to create sustainable competitive advantage based on operational effectiveness. Porter has attempted to prove his position by analyzing Japanese companies, recognized as some of the world leaders in effective operations, and pointing out their failures in the past 20 years as evidence that operational effectiveness is an unsustainable strategy.

From a more in-depth point of view on various top-class methods of improving operational effectiveness, such as Lean, these statements sound extremely strange. The ultimate Lean company, Toyota, remains the most profitable car manufacturer in the world, and is currently producing profits that equal the sum of profits of its two nearest rivals, Volkswagen and GM.

Porter’s argument states that industry best practices are easy to copy, and indeed, that US companies were relatively easily able to copy the operating models of Japanese companies in the 1990s. This reminds me of a story I read in Mike Rother’s Toyota Kata (which, by the way, is one of the best books on Lean): Several years ago, Toyota was happy to show its factories to competitors, who were eager to copy “best practices” for use in their own plants. One such best practice was the use of flow racks. However, a few years later, when most US plants had flow racks, the Toyota plant had got rid of theirs. They had simply evolved beyond that point.

Indeed, when it comes to best operational paradigms, instead of mere ways to arrange activities at a single point of time, companies have significant difficulties in copying them. This is the point where we need to adjust and augment Porter’s frameworks with a resource-based view of competitive advantage, in particular with dynamic capabilities.

Resource-based view on competitive advantage and dynamic capabilities

According to the resource-based view (promoted, among others, by Richard Rumelt and David Teece), resources can indeed be a source of competitive advantage, and even the source of sustainable competitive advantage. In order for this to be the case, these resources have to fulfill each of the following four criteria:

- Valuable. A resource must be an important part of a value-creating strategy. However, this is not enough, because this criterion is no different from Porter’s view, according to which such differences are easy to remove.

- Rare. The resource must also be rare. Again, otherwise everyone in the industry could easily get their own such resource.

- In-imitable. The resource cannot be perfectly copied. Otherwise, competitors could build their own resources in a short time.

- Non-substitutable. The resource must not have substitutes. Otherwise, competitors could replace the resource with a different means to an end and remove the competitive advantage.

What are resources? Resources are factors controlled by a company. One way to categorize and think about resources is to split them into tangible (transferable) and intangible (intransferable) assets and processes.

- Tangible people/assets: Cash, plant, patents, talent.

- Tangible systems/processes: Contracts, alliances, IT systems.

- Intangible people/assets: Brand, reputation, loyalty

- Intangible systems/processes: Culture

The resource-based view has evolved further to consider that when resources are integrated, they give rise to capabilities that the company is then able to leverage in order to gain competitive advantage.

However, in practice most capabilities can eventually be copied. Just consider the flow racks at Toyota: the ways to use flow racks, the capability built on those and other resources, were copied by other companies. But wait, by the time they were fully copied, Toyota had already moved on to do different things! This is the domain of dynamic capabilities.

Dynamic capabilities refer to the ability of an enterprise to shape, reshape, configure, and reconfigure assets in order to respond to changing technologies, markets, and paradigms. The fact that many companies that exhibit these qualities have based their operations on Lean principles, opens an interesting avenue for future research into the strategic significance of Lean.

Conclusions

Porter’s frameworks, the five forces analysis and the value chain analysis, remain vitally important. In order to carry them out properly, it is important to recognize the need to carry out environmental analysis, stakeholder analysis, and competitor analysis.

Furthermore, they need to be augmented by capability analysis with a special focus on dynamic capabilities that open up strategic opportunities not grasped by Porter’s frameworks. By combining all of these, an enterprise can get a good grasp of its strategic position.

Photo: Analysis by Simon Cunningham, Lendingmemo (CC)